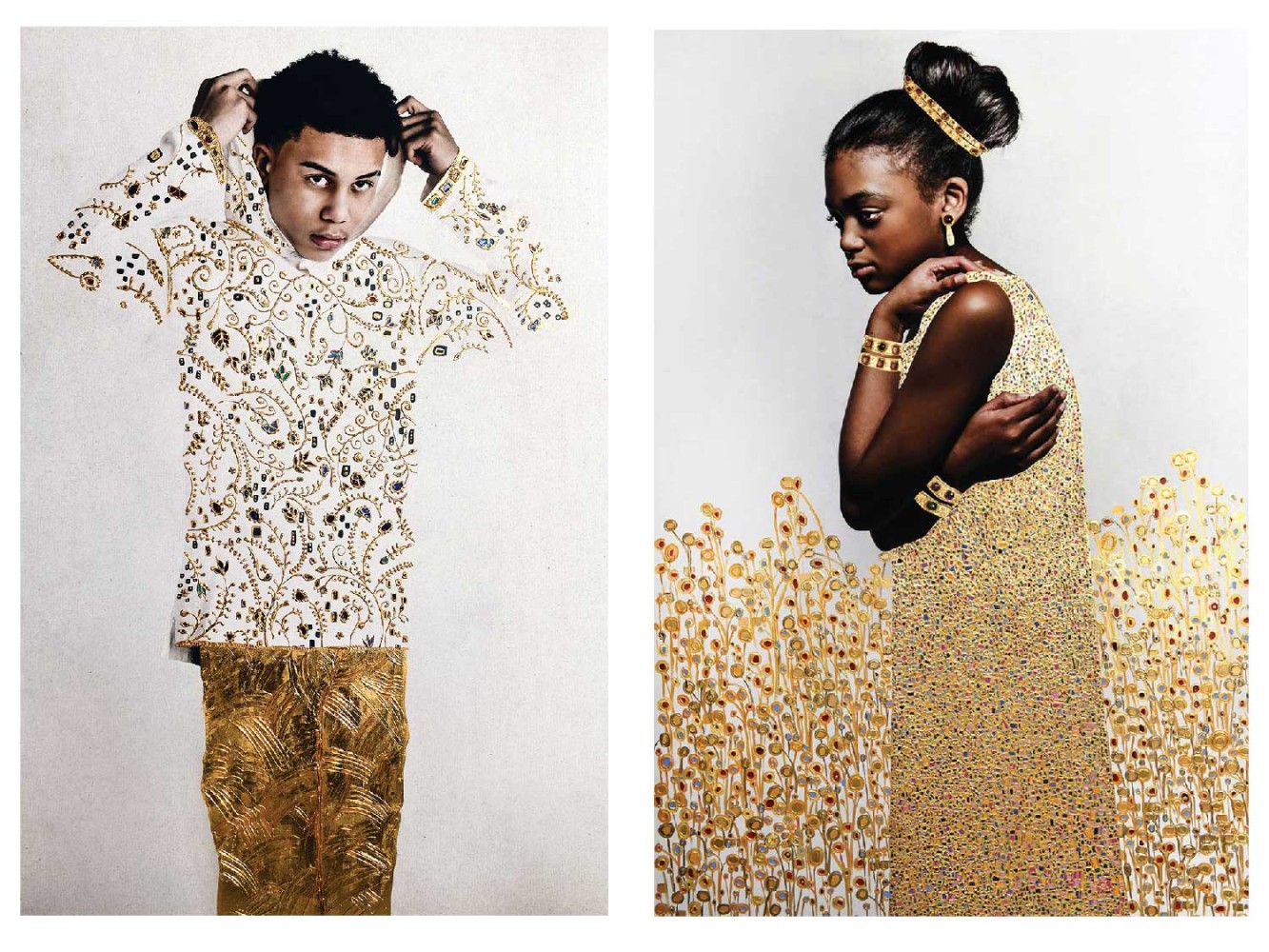

Much of her work shares an aesthetic sensibility with the paintings from Gustav Klimt’s golden phase. The Austrian symbolist painter, known for his intense, gilded artworks suffused with romantic intimacy, is indeed an influence. Klimt used textured mosaic gold motifs in detailed, intricate, beautiful patterns that mimicked what he saw in Byzantine relics. While Chatmon’s use of pattern and color is very similar to Klimt’s, her intentions are not at all the same. What she wants to emulate in her own art are the feelings of regality, magnificence, and beauty she feels when she views his work. “I am looking to convey to the people who sit for me that they are important, they are valuable, they are beautiful,” she explains.

Before becoming a fine artist, Chatmon, who had an early background in theatrical arts, worked as a designer and a commercial photographer. It was only after her father passed away that she started to reassess her own potential. She had been very involved in her father’s care while he was ill, and before he passed away, he gave her important counsel. “He just said: ‘The way that you’re doing all of these things for me, why don’t you try to go that hard for your photography?’” Chatmon recalls. After her father passed, Chatmon tried to push through her grief. “Part of me just wanted to do nothing at that point,” she says, “and then the other part of me wanted to make him proud and do what he told me.”

Soon after, Chatmon began to feel differently about her own role as a parent. “Losing him made me think about how my kids would feel without me. What will they do? With everything that was happening in the world, the thoughts of leaving my kids behind weren’t sitting well with me. I then started focusing on creating artwork.” And her way of doing that was to create beautiful portraits of Black people, art that reflects the world she wants her children to live in. “Me and my kids were going to marches and protests, donating to different organizations, but I kept thinking: What more could I do?” It wasn’t until the Maryland-based artist began to ask herself subsequent questions such as “What am I doing to contribute to that world that I want for my children?” that new concepts and themes began to guide her images. Pivotal queries such as “How can I contribute to some sort of change?” further informed her process, until finally she allowed her photographs to speak for her. “The work,” she says, “became more powerful than anything I can say.”

“I’ve always known I’m a Black woman,” she says, noting the inequality she witnessed and experienced while growing up. After becoming a mother, her activism began to germinate and she instinctually started thinking about the implications of creating a better world for her family. “Having children confirmed that discrimination of any kind is not okay for my children,” she says. “All of my concerns and all of the emotions [connected] to them are poured into the work,” she says. Her aim is to impart those feelings of excellence she sees in her subjects and in the future of Black art. Chatmon wants anyone looking at her art to feel the same sense of power she felt when she first encountered a Klimt painting: “I want the viewer to feel those feelings of regality, of magnificence.”